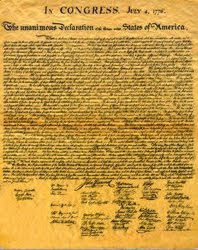

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." — Declaration of Independence.

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." — Declaration of Independence.While the Fourth of July is a largely American affair, the document that laid the foundation of what would become the United States made a statement that exceeded the confines of a handful of colonies. It set forth a declaration that the governed could alter or abolish any government that usurped the unalienable rights of the people — an idea that was not confined to the colonies but born, in part, from the thinking of John Locke, who believed in a limited government bound by a social contract.

Locke, an English philosopher and physician, was one of the most influential contributors to the Age of Enlightenment, a cultural movement in 18th century Europe that sought to promote reason and advance knowledge. Locke was not alone. Baruch Spinoza (Dutch Republic), Pierre Bayle (France), François-Marie Arouet a.k.a Voltaire (France), and Isaac Newton (United Kingdom) had advanced elements of the thinking behind it.

Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and other founding fathers were only a few of the people influenced. The intellectual reasoning had spread across Europe, notably England, Scotland, the German states, the Netherlands, Russia, Italy, Austria, and Spain. It's also why the American Declaration of Independence had a profound impact in the world — concisely articulating the statement before outlining a list of grievances against its government (which was the majority of English Parliament despite the document citing the King of England as the primary culprit).

Writing The Declaration Of Independence.

A few years ago, Stephen Lucas wrote The Stylistic Artistry of the Declaration of Independence, which discusses its literary qualities and its rhetorical power. Among the properties that Lucas points out, the most prominent ten include:

• Clarity. The entire piece uses the most simple and direct language of the time.

• Concise. The document does in 202 words (The Preamble) what it took Locke thousands to do.

• Flow. Not only does every sentence flow into the next, but each word follows another.

• Rhythm. Every sentence is carefully balanced, with significance placed on alliteration (the ear).

• Structure The piece is carefully crafted to deliver a powerful sense of structural unity.

• Objectiveness. The focus on empirical reality rather than interpretations of reality.

• Imagery. The infusion of descriptive words that show the reader rather than merely tell them.

• Emotional. The ability to be human, making an argument for not only the head, but the heart.

• Ambiguity. Each grievance presented is tied to specific events, but names and places are omitted.

• Conclusion. In the conclusion sentence, it reinforces a trilogy of things worth fighting for.

Rarely do politicians employ such literary purpose in their propositions today. And neither do most writers when they set out to make a case on any number of subjects worth writing about. Incidentally, all of them brush up against the five elements of writing to include within any piece of prose or content: clear, concise, accurate, human, and conspicuous.

Are We Due For A Second Age Of Enlightenment?

One of the most profound details of the Declaration of Independence (that I learned a few years ago), was a significant edit made by Franklin. Originally, Jefferson had borrowed from the more popular trilogy spoke of during the day — life, liberty, and property. It was Franklin who struck down property and inserted the less tangible pursuit of happiness.

While some see the edit as a minor nuisance to provide for more intangible and higher cause, I sometimes wonder if Franklin also intended to avoid the trappings of tangible goods being assigned to government. We can read as much in the Bill of Rights, which was created as a condition to the U.S. Constitution (1787), insisted upon by men who wanted to preserve the influence from the Age of Enlightenment well into the future of the country. With property comes the power to move toward tyranny.

We might even see the problem with some governments' increased focus on property today as opposed to providing for the security of life (protection from aggressors), liberty (freedom), and pursuit of happiness (a free marketplace of ideas). As governments borrow against the assets of the people and/or regulate individual financial prowess, it positions such governments not only to enslave a people, but also promises to enslave their descendants as slaves to such debt, thereby making it nearly impossible to pursue happiness, or perhaps enlightenment as intended, without a mountain of preexisting shackles of constraint.

We might even see the problem with some governments' increased focus on property today as opposed to providing for the security of life (protection from aggressors), liberty (freedom), and pursuit of happiness (a free marketplace of ideas). As governments borrow against the assets of the people and/or regulate individual financial prowess, it positions such governments not only to enslave a people, but also promises to enslave their descendants as slaves to such debt, thereby making it nearly impossible to pursue happiness, or perhaps enlightenment as intended, without a mountain of preexisting shackles of constraint. At least, that is what I intend to ask my children consider when they are older. While there are those who believe the happiness of the many outweighs that of the few; there are also those who believe that the insistence any individual — endowed with the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — be forced to relinquish such rights is nothing more than the embodiment of mass selfishness.

And it seems to me that the founding fathers belonged to the latter grouping, shedding obligation from its sovereign, who had apparently forgotten that any government derive their rights from the free people they govern and not the other way around. Leadership, for example, is not the prize for a despot who can override a nation's social contract, but rather an honor to protect and preserve that very social contract that grants that honor. At least, I think so. Good night and good luck.

Have a happy and safe Fourth of July, with at least a sliver of time in between the barbecues and fireworks to contemplate its meaning. And for all my non-American friends, take a moment to consider that while our celebration is American, the foundation of this celebration is truly the collective result of enlightened people across Europe spanning hundreds of years.