Perhaps even more so with the launch of Facebook Sponsored Stories, there is increasing division about how marketers might approach Facebook. There are four primary approaches that marketers can make in any combination. And depending on the mix, those efforts produce two types of outcomes — collections or communities.

Perhaps even more so with the launch of Facebook Sponsored Stories, there is increasing division about how marketers might approach Facebook. There are four primary approaches that marketers can make in any combination. And depending on the mix, those efforts produce two types of outcomes — collections or communities. The four approaches to Facebook.

Invitation.

The invitation is the most prominent tactic, which commonly includes listing the address on any number of marketing materials. By adding a button on websites or icons on print advertisements, companies share that they exist on Facebook.

It's self-selected, usually undertaken by one of three types of fans — loyal customers, prospective customers, and perpetual dreamers (with the latter existing for select brands). For example, Porsche is made up of people who own Porsches, people who are considering a Porsche, and people who've always dreamed of owning a Porsche but more than likely never will.

There are spammers too, but well-managed accounts can deal with them effectively enough. Deleting spam posts (irrelevant content) or banning people who have no purpose other than tossing up junk links can be removed. But for the most part, the only accounts that keep them are number focused.

Introduction.

The introduction generally consists of well-placed advertising that attracts people to the site. It became even more common when Facebook launched its advertising program.

The introduction generally consists of well-placed advertising that attracts people to the site. It became even more common when Facebook launched its advertising program. In this case, the primary driver was that a marketer could target specific demographics, proximity, or an expressed interest in something. Deciding which works best for the Facebook page is as varied as the account type. For example, a restaurant might benefit from focusing on proximity or a specific product might appeal to a certain demographic or a publication might write about a specific interest.

Advertising for a Facebook page can be added off the page too. But mostly, Facebook's program works well enough inside the platform. It makes more sense to promote a website beyond the program because people can always connect via the page.

Not all introductions are paid, of course. The sharing function within Facebook is generally well liked. People share topics of interest all the time with their friends. But it also relies on the strength of the page community.

Sponsored.

The newest advertising feature on Facebook empowers marketers to capitalize on shared stories by turning them into advertisements. The position of Facebook is that since the person already shared or endorsed or liked a page, someone else sharing this information (including a marketer) isn't any different.

While the shared stories concept has raised privacy concerns (including some advising people not to like anything), Facebook does have a point that it's not very different from the way the concept works today. Some marketers, brands, and companies have been sharing content all along. This simply moves it to the sidebar.

But the bigger question to ask is what kind of person does it attract to the page. If the consumer is drawn more by the relationship to another person and less for some of the reasons expressed in the other approaches, a marketer could gain more connections but not necessarily more interest in the product, service, store, or content.

Bought.

While just as old as any other approach, some people very literally purchase connections. They earn their "likes" by either purchasing connections outright, any number of link exchange programs (points or mutual), or coupon bribes and discounts.

While the latter doesn't seem to have as many issues as the first two, the primary objective of those who engage in any kind of purchased connection schemes is to run up big numbers. But numbers aren't a very good measure online. At least, not as good as some people would have you believe.

While it is true that popular pages tend to increase the likelihood of a page being liked, numbers alone do not guarantee it. People often look at several factors before liking a page, including its interaction with the members and among members.

The Two Types Of Divergent Outcomes.

The Capture.

Marketers that are intent on capturing fans ought to have no real problems. But the downside to chasing numbers is there are no real benefits either. There might even be unseen challenges.

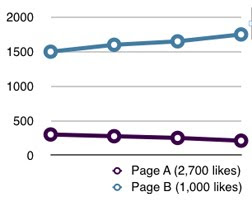

Someone we work with used this approach on the front end of the Facebook experience and quickly captured 2,700 "likes" without much sweat. They were captured in about one month. However, what most people will never see is the story behind the scenes. These 2,700 connections have an interaction of 300 visits every 30 days and falling. And about 1,500 page views over the same period.

Even when new customers or self-selected connections join the page, the silence of those members encourages them to do the same, which is virtually nothing.

The Community.

Conversely, there is a page that we manage that was operated on an organic-only approach, which means the page only used self-selected community members — either invitations to people visiting the site or people with a specific common interest.

Conversely, there is a page that we manage that was operated on an organic-only approach, which means the page only used self-selected community members — either invitations to people visiting the site or people with a specific common interest. It had a modest following of 1,000 members. It took approximately seven months. However, behind the scenes, it has an active and growing community with 1,500 visits and growing at a steady, if not exponential, pace. And about 35,000 page views over the same period. When new connections are made, they are much quicker to like, share, and comment on the page just as they see other members do.

Interestingly enough, which touches on the concept of marketer-selected shared stories as opposed to friend-selected shared stories, some of my friends joined the 1,000-member page but never participate. Conversely, non-friends on the page have become friends over time through repeated interactions.

Is Friendship Enough?

Facebook says that its sponsored story tests had higher recall and were much more likely to result in an action (such as a friend liking a page too). However, our research is continuing to show that overemphasizing a friendship connection over a common interest connection actually drags down the interactions of the community.

The reason is psychology. Sometimes people like a page because a friend likes it. They may even recall which friend likes it and why. Liking it might even be less of an expressed interest in the page as much as it is a nod recognizing that a friend likes it.

However, such a scenario is much different than two friends who like the same things on the same page. In those instances, the two friends are much more likely to interact with the page, and perhaps, reinforce their mutual interests.

This isn't to say the sponsored story concept isn't intriguing. It has the potential to work, especially with the right company. The Starbucks example in the video is a good one. I can see how it might work for a restaurant. But for something else — let's say an environmental survival store — people might like the page because they want to support their friend's interest and feel more environmental for the day. But, they are likely to never visit the page again let alone buy anything from the company.