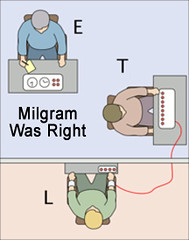

In 1963, Stanley Milgram gave the world a glimpse into obedience by publishing the results of his experiment in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. I learned about the study in college.

The experiment, conducted at Yale University, tested how much pain one participant would inflict on another, provided the participant inflicting the pain would relinquish responsibility to the person they perceived as an authority.

Although the experiment was staged (the person enduring the pain was a actor) and no one was injured, Milgram found that 65 percent of participants would administer an electric shock of what they believed to be 450 volts. Even more surprising, not one participant refused to administer shocks before the 300-volt level, despite several switches clearly marked “danger: severe shock” and the actor complaining of chest pain, banging on the wall, or dropping silent.

With light to moderate prodding, an authority figure in the experiment was able to convince the participant to deliver electric shocks. Some would protest, but continue to “shock” the actor nevertheless.

Understanding Obedient Staff Behavior.

Understanding Milgram’s experiment was followed by strip search prank call several years ago. It was not an experiment. It involved a caller claiming to be the police and instructing fast food managers to strip search employees. In more than 70 reported cases, managers surrendered personal responsibility to an authority figure, becoming like a puppet, and demanded employees remove their clothes.

By comparison, the notion that staff at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada would blindly follow the instruction of administrators to reuse vials of single-dose medicine would likely take less surrendering of responsibility to a higher authority, especially one who had served on the board of the Nevada Board of Medical Examiners.

Why? Proximity to the authority figure. Perceived level of authority. Assurances of a minimal risk. Other nurses already practicing the procedure. And on. And on.

It the only answer for people still wonder why they didn’t stop the practice at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada. Objectivity was sacrificed in favor of perceived acceptance. As one CDC officer reported it: the center’s practices to be so obviously dangerous that it was like “driving the wrong way down the freeway.”

I feel the same way about the center's crisis communication plan. It's like watching a horror show of a horror show, where you watch the next victim stumble up stairs with a flashlight.

The latest update: The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department and county prosecutors opened a preliminary criminal investigation. These investigations join inquiries by the FBI and the Nevada attorney general’s office.

Add to all this news an endless stream of sources being tapped by the media, including a very telling and almost incoherent interview with the center’s recently hired third-party crisis expert. Somebody forgot to tell her she wasn't a spokesperson.

Employees Need To Learn To Say No.

Comedian George Carlin includes it in his bit. He says people are too fat and happy to question authority. He's right. It happens all the time.

Even on social networks, it's obvious people blindly follow perceived authority figures, sometimes even participating in a “pile ons” just to be accepted. There is no concern for facts. Most online diatribe can be traced back to obedience and acceptance. It happens everywhere in places all over the world, places just like the Endoscopy Center.

There is only one lesson, and more employees could learn it:

• Th nurses could have complained to the administration that the practices were unsafe, refused to perform them, and demanded correction.

• Upon administrative insistence, the nurses could have told the center to correct its practices or report the incident to county health officials.

• Upon insistence or further inaction, the nurses could have resigned and immediately reported the infractions to county health officials.

Three simple steps could have protected thousands of people from being at risk of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Unfortunately, no one was up to the task. In all the world, only a mere 10-25 percent of people would have been willing to step up to the plate, depending on the country where they were raised.

The experiment, conducted at Yale University, tested how much pain one participant would inflict on another, provided the participant inflicting the pain would relinquish responsibility to the person they perceived as an authority.

Although the experiment was staged (the person enduring the pain was a actor) and no one was injured, Milgram found that 65 percent of participants would administer an electric shock of what they believed to be 450 volts. Even more surprising, not one participant refused to administer shocks before the 300-volt level, despite several switches clearly marked “danger: severe shock” and the actor complaining of chest pain, banging on the wall, or dropping silent.

With light to moderate prodding, an authority figure in the experiment was able to convince the participant to deliver electric shocks. Some would protest, but continue to “shock” the actor nevertheless.

Understanding Obedient Staff Behavior.

Understanding Milgram’s experiment was followed by strip search prank call several years ago. It was not an experiment. It involved a caller claiming to be the police and instructing fast food managers to strip search employees. In more than 70 reported cases, managers surrendered personal responsibility to an authority figure, becoming like a puppet, and demanded employees remove their clothes.

By comparison, the notion that staff at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada would blindly follow the instruction of administrators to reuse vials of single-dose medicine would likely take less surrendering of responsibility to a higher authority, especially one who had served on the board of the Nevada Board of Medical Examiners.

Why? Proximity to the authority figure. Perceived level of authority. Assurances of a minimal risk. Other nurses already practicing the procedure. And on. And on.

It the only answer for people still wonder why they didn’t stop the practice at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada. Objectivity was sacrificed in favor of perceived acceptance. As one CDC officer reported it: the center’s practices to be so obviously dangerous that it was like “driving the wrong way down the freeway.”

I feel the same way about the center's crisis communication plan. It's like watching a horror show of a horror show, where you watch the next victim stumble up stairs with a flashlight.

The latest update: The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department and county prosecutors opened a preliminary criminal investigation. These investigations join inquiries by the FBI and the Nevada attorney general’s office.

Add to all this news an endless stream of sources being tapped by the media, including a very telling and almost incoherent interview with the center’s recently hired third-party crisis expert. Somebody forgot to tell her she wasn't a spokesperson.

Employees Need To Learn To Say No.

Comedian George Carlin includes it in his bit. He says people are too fat and happy to question authority. He's right. It happens all the time.

Even on social networks, it's obvious people blindly follow perceived authority figures, sometimes even participating in a “pile ons” just to be accepted. There is no concern for facts. Most online diatribe can be traced back to obedience and acceptance. It happens everywhere in places all over the world, places just like the Endoscopy Center.

There is only one lesson, and more employees could learn it:

• Th nurses could have complained to the administration that the practices were unsafe, refused to perform them, and demanded correction.

• Upon administrative insistence, the nurses could have told the center to correct its practices or report the incident to county health officials.

• Upon insistence or further inaction, the nurses could have resigned and immediately reported the infractions to county health officials.

Three simple steps could have protected thousands of people from being at risk of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Unfortunately, no one was up to the task. In all the world, only a mere 10-25 percent of people would have been willing to step up to the plate, depending on the country where they were raised.