When applied to social media, organic doesn't resonate with everyone. There is a reason it doesn't. It has become one of several analogies that have been distorted to fit any number of new meanings (much like sustainable did). And most of those distortions were all aimed at making fake look better.

When applied to social media, organic doesn't resonate with everyone. There is a reason it doesn't. It has become one of several analogies that have been distorted to fit any number of new meanings (much like sustainable did). And most of those distortions were all aimed at making fake look better.The original meaning as it was applied to content is much more holistic. Let's stick with its content origin today; the analogy came from food. Applied to blogs, it draws a distinction between processed and organic much like Hollywood draws a distinction between a celebrity and an actor/actress. One is popular; the other has talent. Sometimes, but rarely, one can be both.

The Three Types Of Content Farmers.

Processed Content. Convenience food is commercially prepared designed for ease of consumption. While often popular, most convenience foods contains saturated fat, sodium, and sugar. They provide little to no nutritional value but tend to have enough flavor to appeal to a mass audience. To keep up with demand, some farmers might use pesticides and chemical fertilizers to speed things along.

It applies to social media in that some of the most popular blogs on the Web become automated over time. Their owners have formulas for almost everything they do, including how to pick topics, write posts, and distribute to more consumers. Many of them have a following of distributors; people will promote anything they do regardless of quality. A few of them cut corners.

Organic Content. Organic foods are produced using environmentally sound methods that do not involve modern synthetic inputs such as pesticides and chemical fertilizers. They do not contain genetically modified organisms, and are not processed using irradiation, industrial solvents, or chemical food additives. Not only is it better for you, but is tastes better too. The only downside is that it takes much longer to prepare.

It applies to social media in that some of the less popular blogs carry superior quality content, with every post being well thought out and original. Sometimes these authors pick up on other people's ideas and expand upon them, but always with their own research and added value. In general, they tend to be equal parts: inspired by offline events and trending topics. The advice they share is almost always grounded in communication strategy.

Private Label Content. This is where most farmers started hundreds and thousands of years ago. The results are often mixed. Some gardeners have green thumbs and some do not. There are any number of reasons for the variations. It could be the climate, soil conditions, seeds, talent, or perhaps just never finding whatever it is that they may become passionate about.

It applies to social media, with the exception that we can capture a snapshot of where they start as opposed to real farms that are in operation today. Most bloggers start with a few posts, testing various crops to see what what works best for them. If one sticks, they start sowing a field. Not all of these private farmers do, nor will all of them stick with it. The bulk will give up for whatever reason.

The Fresh Content Project.

In tracking about 250 blogs, daily, for almost a year, we found something interesting but not surprising. The analogy of processed vs. organic vs. private label fits. It even fits as a mix of the blogs we covered — originally about 100 and eventually about 250.

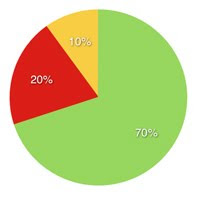

Specifically, about 10 percent of the blogs covered were processed (A List), 20 percent organic (B List) and the bulk, 70 percent, were made up of private gardeners (C-Z Lists). This was not by design. It just happened to break out this way.

Specifically, about 10 percent of the blogs covered were processed (A List), 20 percent organic (B List) and the bulk, 70 percent, were made up of private gardeners (C-Z Lists). This was not by design. It just happened to break out this way. The original list was compiled from several dozen social media lists that had been previously published by people we knew. From these lists, we built a Twitter list with two purposes.

First, all their blogs were reviewed for consideration. Second, blogs that they tended to recommend with some frequency were also considered. We also added some additional blogs after we were introduced to new authors who wrote guest posts for one of the blogs we were already covering. There was a vetting process.

We also did not make any distinction between multi-author blogs and single-author blogs. Instead, we considered these authors a variation of sharecroppers. Or, in other words, they might have been private gardeners but planted a fresh idea on real estate owned by someone else. More people are exposed to their stock, but everybody remembers the blog they write for as opposed to who wrote the content.

Content Farmer Consumption.

While this is an extremely rough snapshot (something we'll revisit before any final report), we estimate that more than 50 percent of the content consumers rely on A-List content farmers for information. Specifically, they are popular authors.

It's not surprising. Consumers tend to bookmark, friend, follow, and subscribe to people who seem popular. You can only read so many blogs no matter how you stack them. So people gravitate to reading what their friends or associates read, quality content or not.

It's not surprising. Consumers tend to bookmark, friend, follow, and subscribe to people who seem popular. You can only read so many blogs no matter how you stack them. So people gravitate to reading what their friends or associates read, quality content or not. Popular content providers usually have another leg up too. If they speak regularly or have a book published, they attract more followers much in the same way samplers do at supermarkets. Familiarity attracts readers, even if that familiarity is thin.

In contrast, private gardeners are very different. Many are happy with sharing content between a handful of colleagues. Most, but not all, believe that once they have found the right content mix that more and more people will eventually place orders, subscribe, and follow them too. They capture approximately 30 percent of traffic.

Ironically, many private gardeners are also responsible for sending more traffic to the processed content farmers. It might seem odd, but private gardeners are continually telling consumers who enjoyed their cherry tomatoes to follow the A-lister who inspired them. Conversely, few A-List content farmers credit private gardeners in the same way.

Quality Content Comes From Everywhere.

While I won't say that every private gardener can produce quality content, I can say that any private gardener with experience and talent is capable, whether they own their own space or want to be a sharecropper. In fact, during the experiment, even authors with no prior experience were frequently picked as having written the best post of the day.

It's much like any garden with a talented gardener. You might not find their brand at the supermarket, but you will enjoy the salad they serve. Collectively, although many are hit and miss, private gardeners served up 35 percent of all fresh picks.

It's much like any garden with a talented gardener. You might not find their brand at the supermarket, but you will enjoy the salad they serve. Collectively, although many are hit and miss, private gardeners served up 35 percent of all fresh picks. Sometimes A-List providers can too. Much like every vineyard has select wines, some A-listers maintain the private garden that preceded their massive operations. And occasionally, though only a sliver in comparison to the quantity they produce, you can usually find some quality from time to time. They served up 20 percent of all fresh post picks.

The bulk of fresh content picks came from organic farmers. They generated more than 45 percent of the highest quality posts. And, even when their posts were not "fresh picks," we frequently shared their work as an "also read" pick across various social networks.

Why Popularity Does Not Produce Comparable Quality.

Once upon a time, almost everyone who wrote a blog could be considered a private gardener. But as social media became mainstream, many were faced with a choice much like farmers — automate or retain the quality that made them popular.

Some remained private gardeners or dropped out. Some shifted the priorities of their business with more time to expand while retaining quality. And others became automated, propelled mostly by popularity. The tells are relatively apparent.

Processed content inevitably includes a post or two or 20 about how awesome the author is or how some lesser blogger picked on them or how they captured 5,000 followers in a weekend or how you have to have as many followers as them to be taken seriously. If posts like that still manage to be shared by 250 people or more, their blog can rightly be likened to processed yellow American cheese singlesconveniently packaged in individual wrappers.

While I am not suggesting abandoning the popular communication bloggers outright, the fresh content experiment did find that organic authors invest more time to produce quality content for a significantly smaller audience share. Proportionately, in terms of quality, most people are following the right people.

The best place to find quality content is to start stacking the deck with more organic content providers and frequently sampling private gardeners who have the potential (if not the passion) to become organic farmers. The only downside is that it takes a little more time to find them. However, it seems a small price to pay considering we all know what too much processed content can do over time — it could make your entire communication strategy flabby and reactive.

This is the fifth lesson from the Fresh Content experiment, which tracked 250 blogs for almost a year. The experiment focused on the quality of the content and not the perceived popularity of the authors. Next week, we'll conclude with a list of picked authors and any plans to produce a short e-book.