For the last several years, when I've taught social media at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, I've warned students away from getting caught up in the duality of the field. In some ways, it's not just the field. Duality is the way people are hardwired.

Just as we have two eyes and two feet, duality is part of life. — Carlos Santana

Ike Pigott mentioned it yesterday, using Hemispheres by Rush as an analogy. But another story that piqued my interest was one by Geoff Livingston, writing for Mashable.

His topic about crowd-sourcing lands within the spectrum of duality. Much like bands, social networks and online communities exist because of crowds. However, crowds are attracted to uniqueness. You have to balance the effort, in being yourself while delivering up what people want.

Livingston penned a solid post, and I encourage you to read it there. The segment I wanted to touch on today is community management, especially rule enforcement (which is his forth point). It's a compelling argument for social media, because it tends to cut against the grain. Community-centric behavior needs to be enforced, he says. Let the community run wild, most say.

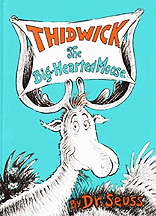

Everything you ever needed to know about social media is already written by Dr. Seuss.

Seriously. Dr. Seuss covered most social media topics well before social media was even a glimmer in someone's eye. And when it comes to managing communities, he included a warning story of sorts within Thidwick, The Big-Hearted Moose.

Seriously. Dr. Seuss covered most social media topics well before social media was even a glimmer in someone's eye. And when it comes to managing communities, he included a warning story of sorts within Thidwick, The Big-Hearted Moose. Thidwick, being the big-hearted moose that he was, allowed a Bingle Bug to climb on his antlers and enjoy the ride. The Bingle Bug was appreciative and grateful on the front end. But then, over time, he started inviting folks to the party. Namely, he invited a Tree-Spider, a Zinn-a-zu bird (and his wife), a woodpecker, a family of squirrels, a bobcat, a turtle, a fox, some mice, 62 bees, and even a bear. All of them made their home on Thidwick's antlers.

That became rather uncomfortable for the big-hearted moose. And it posed an even bigger problem when Thidwick needed to cross the river. The crowd promptly voted him down, even though that meant Thidwick would not be able to reach the moose-moss on the other side of Lake Winna-Bango.

Fortunately for Thidwick, at a critical juncture in the story (after being chased by hunters), he sheds his antlers as all moose do about once a year and that was that. He was able to join his friends. The ill-mannered guests, on the other hand, were not so lucky. They ended up on the hunting lodge wall, horns and all.

Now, of course, most people operating in social media cannot afford to simply dump their communities like Thidwick did. You have to find a better way than that (although several blogs, communities, and networks have closed their doors when things went out of control).

And that is where community management comes in to play. The day you have to start enforcing rules is the day you know that you already let things get out of control. For Thidwick, that point was exemplified as the woodpecker drilled holes in his horns. It was already too late.

Community enforcement begins with guidance.

The problem that some social media programs have is, much like Thidwick, they allow the crowd to grow without any thought whatsoever (other than elation that they are attracting people at a steady clip and cheering social media numbers). And by the time problems start to appear, little cracks in the community, it's already too late.

The problem that some social media programs have is, much like Thidwick, they allow the crowd to grow without any thought whatsoever (other than elation that they are attracting people at a steady clip and cheering social media numbers). And by the time problems start to appear, little cracks in the community, it's already too late.Since I first starting working with social media, I have had the ugly task of quelling several network conflicts, including a few that were outright rebellions. It wasn't very difficult for me to set things right, but it was for various owners. In every case, the cause was a neglected community. Almost overnight, or so it seemed, they had attracted a crowd — but the wrong crowd.

That is also why, as Livingston pointed out in his post, Pepsi Refresh had to adjust and enforce its rules address fraudulent voting. That is why Digg dumped several features needed to create a sense of community, but also made it super easy to game the system with reciprocal voting. And it is also why none of the Twitter influence algorithms work.

Ergo, if you want to develop a Christian network, attracting an abundance of atheists might not be such a good idea (or vice versa). However, a few, assuming they maintain decorum, could keep things challenging enough to avoid bubble syndrome. And that's my point. Community management is about being proactive in the shaping from the ground up and forever. It requires balance.

Even Thidwick, whom we are supposed to sympathize with (given the story is a lesson for guest behavior), was partly to blame for his predicament. He assumed that the more he catered to his guests (and the more guests there were) somehow equated to having a bigger heart. He was wrong. Sometimes having a bigger heart means enforcement, but all too often enforcement also means that the manager neglected a problem that already existed.

Guidance before problems start is already the remedy. And the same holds true in inner office disputes too. While there is the occasional bad apple hire, most inner office issues are the result of a community operating without proper guidance. Ergo, had Thidwick drew the line with the Bingle Bug and Tree-Spider, the story would have had a happier ending for everyone.